African court’s landmark ruling gives hope to rural people across the continent

Liz Alden Wily, Leiden University

The still new African Court on Human and Peoples’ Rights has issued a landmark judgement for marginalised communities across Africa. It ruled that the Kenyan government violated the rights of the Mau Ogiek people by evicting them from their ancestral land in the Mau Forest complex.

Before taking their case to the African court, the Mau Ogiek had waged a long battle in a national court against routine evictions which the government has justified on the grounds of concerns about the environment.

The court for human and people’s rights rejected these claims. It concluded that eviction from their ancestral forest territories violated the African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights, the founding continental law to which all members of the African Union are party.

The court was established by African states in 2006 to ensure the protection of human and peoples’ rights in Africa. It has so far finalised 32 cases. Its work compliments that of the African Commission on Human and Peoples Rights – which acted on behalf of the Ogiek. The Ogiek case is the first time the court has ruled on an indigenous peoples’ rights case or in a case with mass human rights violations indicated.

This is why the decision matters a great deal. Not only for Africans who define themselves as indigenous people but for all rural dwellers who own land on the basis of customary law. Their numbers are expected to rise to around one billion by 2050. Around two-thirds of their lands are not farms but forests and rangelands critical to their livelihoods.

Unfortunately, while the ruling is legally binding, the court will have to work hard to ensure compliance. The Kenyan Government is yet to implement a 2009 quasi-judicial ruling by the African Commission on a similar issue. No doubt this non-compliance encouraged the commission to forward the case to the African Court.

Linking land rights and conservation

The court made some key observations in its ruling. These included:

-

The profound attachment that Ogiek hunter-gatherers have to their environment and the way in which this shapes every aspect of their society, irrespective of modernising lifestyles.

-

Their long history of subjugation and marginalisation, including denial of land rights that have been granted to stronger tribes. The first major forcible evictions of the Mau Ogiek date back to the 1910s under the British colonial government.

The court also concluded that evicting the Ogiek is neither

[necessary] nor proportionate to achieve the purported [government] justification of preserving the natural ecosystem of the Mau Forest.

On the contrary, the court found evidence, that the Kenyan government was responsible for much of the environmental destruction. This included taking land for private settlement (including for politically powerful elites such as former President Moi) and losses through “ill-advised logging concessions”.

The court recognised that the intact forest is infinitely more valuable to forest people than a cleared forest. The Ogiek’s founding traditional beekeeping culture requires complex natural forests to survive, and virtually every ritual and organisational norm is borne from the forest’s existence. “We lose the forest, we lose our society” is a routine refrain among Kenya’s modern forest peoples.

The court’s recognition of this is crucial. The government of Kenya pinned its defence on firstly that Ogiek were no longer solely dependent on hunting and gathering, and secondly that the need to evict them was in the public interest of saving natural forests.

The judges found little to suggest the public interest would be served by this strategy.

Reaping the ruling’s rewards

Who will benefit from this judgement? The answer is: a wide-range of people, as well as policies and institutions.

The first is the court itself. It has demonstrated its autonomy in a continent where judicial independence remains shaky in many states.

Secondly, all indigenous forest peoples in Kenya will find it easier to advance their own claims for recognition as owners of presently classified “government” forests. Around 135,000 members of forest peoples are directly affected – these include the Elgon Ogiek and Sengwer communities.

The case has also given indigenous peoples throughout Africa resounding legal recognition that they exist and are due the support of international law.

And restitution in general will be advanced in Kenya. This is promised in law as one of the remedies for historical land injustices, but it’s never applied.

All customary landowners around the continent can look to the judgement as a source of support for legal recognition of their tenure as lawful possession. While ten or so states have taken this position since the 1990s, it remains weak or absent in 40.

The judgement will also boost conservation strategies that look to communities to conserve vulnerable protected areas. The right to evict traditional owners in the name of conservation has been dealt a body blow.

Implementing the judgement

This is a tricky question. The court ruled that reparations will be decided in a separate decision once it has heard additional submissions from both parties.

The Ogiek were clear on their asks; compensation for the hardships and losses they have endured, guarantees of non-repetition of evictions and denial of their land, cultural and development rights without their consent, and most of all, restitution of their lands and the right to occupy and conserve them.

While the government of Kenya can be expected to protest each demand, and compromises will be made, the court has set the bar high on all counts by establishing that violations have occurred in all these areas and must be remedied.

Moreover, Ogiek asks have the support of Kenya’s new constitution which provides for community lands as a lawful category of property. This includes “the ancestral lands and lands traditionally occupied by hunter-gatherer communities”.

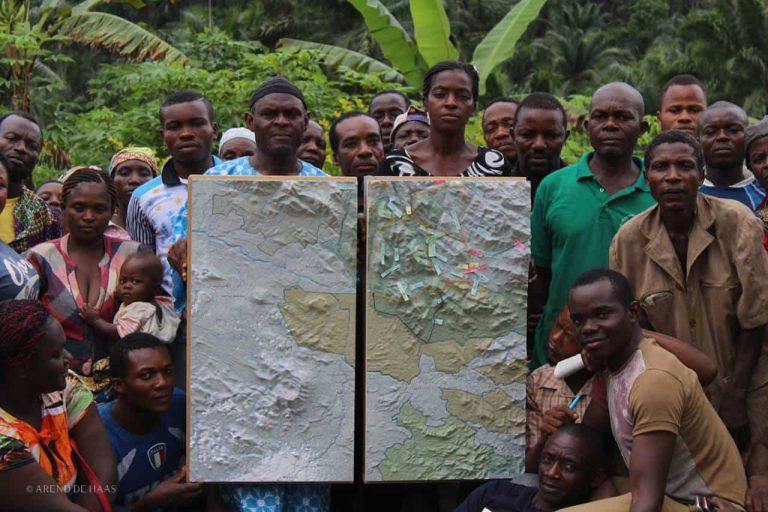

![]() Nevertheless, as ever, on the continent, the surest route to compliance will be pressure from citizens. It is in the interests of at least 18 million customary landholders in Kenya to apply this pressure.

Nevertheless, as ever, on the continent, the surest route to compliance will be pressure from citizens. It is in the interests of at least 18 million customary landholders in Kenya to apply this pressure.

Liz Alden Wily, Researcher/Advocate on Customary Land Rights, Fellow at Van Vollenhoven Institute for Law, Governance and Society, Leiden University

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.

![Let the [RE]CHARGE journey begin: Hitting the road to raise sustainability awareness](https://africanconservation.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/10/eneloop-REcharge-journey-768x512.jpg)